Where Did the Silicon in Silicon Valley Go? The Lessons Everyone in Any Industry Should Learn From

By Brett Fox

Marc Andreessen famously said that the Silicon Valley was “dead” when he got here in the 1993.

And he was right: Software didn’t rule the Silicon Valley in 1993:

Hardware did, and semiconductor companies led the way.

Not anymore though.

I wrote last year about the coming consolidation of the semiconductor industry.

It’s like watching water go down a drain: the water goes faster when it gets closer to the drain.

The rate of mergers and acquisitions is going at an unbelievably fast pace now.

Look at what’s happened just since the beginning of 2015:

- Avago’s proposed $47B merger with Broadcom

- Intel’s proposed $37B merger with Altera

- NXP proposed $12B merger with Freescale

- Cypress’ $5B merger with Spansion

Now, mergers have been part of any business segment since the beginning of time. The difference today is that there are no new companies replacing the merged companies:

New Funded Companies + Existing Companies – Merged Companies = Total Companies

With New Funded Companies essentially at zero, the total number of companies is going to go down.

Why are no new semiconductor companies being funded?

There are new semiconductor companies being formed. However, there are no new semiconductor companies being funded by venture capital firms. Well, the number is practically zero.

There are three key reasons why venture capital firms are not funding semiconductor companies any more:

- Semiconductor industry growth has slowed to roughly 5% per year. Yes, the semiconductor business is still over a $300B market, but growth is slowing.

- VC's believe it takes $70M to get a semiconductor company off the ground and VC's want a 10x return on their investment. I know from personal experience it can be done for considerably less. Ask yourself when the last $700M I.P.O. or sale of a semiconductor company occurred, and you see the problem.

- Most of the semiconductor investors in venture capital have been fired or retired. Venture capital is a kill or be killed business. You get put out to pasture pretty quickly when you don’t return capital to your investors.

These three reasons are a large part of why we are not seeing many semiconductor startups in the Silicon Valley. The real reason?

The technology bubble of 1996-2000 killed semiconductor startups.

Here’s why:

You have to start with the success of semiconductor investments during the bubble.

Valuations of public semiconductor companies during the late 1990’s expanded at a rapid rate. This was especially true for companies focused on wired and wireless communications.

AMCC, Broadcom, PMC-Sierra, and Vitesse were all trading at ridiculous multiples.

These companies used their stock currency to acquire startups in all-stock transactions at outrageous prices.

Many of these startups had very narrow visions: only a few products at best.

VC’s could “flip” companies and get a 10x or greater return on their investment in record time.

This system of rapidly flipping companies led semiconductor entrepreneurs and VC's to feed off each other:

- Entrepreneurs gave VC's what they wanted: narrowly focused companies developing a few products, and

- VC's funded these companies expecting and getting a quick return.

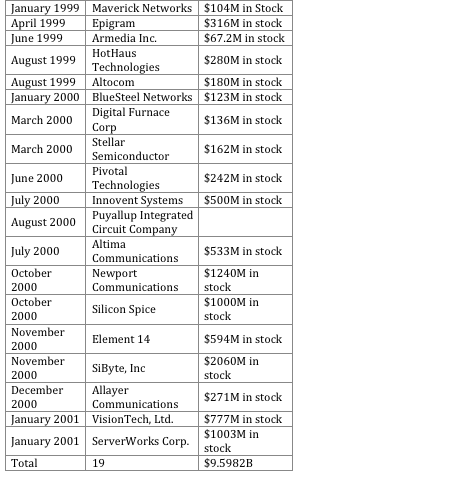

Just look at the deals Broadcom did between 1999 and 2001:

Broadcom’s market capitalization peaked in Q3, 2000 at $60B on revenue of $1.1B. That’s gives Broadcom a price to sales ratio of almost 60!

Broadcom today has a market cap of $32B on revenue of $8.5B and a price to sales ratio of 3.8. Just for reference, Linear Technology has the highest price to sales ratio in the semiconductor industry today at ~7.

It was easy money for everyone.

Semiconductor entrepreneurs thought the road to riches was building these narrowly focused companies. And why wouldn’t they?

It all fit together nicely:

- Companies wanted products to fill out their product lines and…

- Venture capital provided the R&D “venture” money and…

- Entrepreneurs provided the knowhow and…

- Stock market “analysts” lauded each acquisition pushing stock prices ever higher.

There was a massive bubble in semiconductor stocks in 2000 that was ready burst.

Broadcom’s stock fell from a Q3, 2000 peak of $274 to $27 in Q1, 2001.

Need I say more?

Then, the cycle went in reverse:

Companies didn’t have the inflated stock to buy startups for ridiculous valuations anymore, so…

Venture capital firms had to hold the companies in their portfolios for longer and longer times before they could sell them…

For non-inflated valuations hurting the returns for the funds and for entrepreneurs

The problem was that many venture capital firms kept investing in the same, narrowly focused semiconductor companies long after the bubble of 2000. Venture capital firms reached a conclusion:

You can’t make money in semiconductor investments anymore.

VC firms are not wrong.

It is very difficult to make money investing in narrowly focused semiconductor startups that are trying to go head-to-head with the Texas Instruments of the world.

What happens when you can’t make money?

Most VC's funds have partnerships for the 10-year life of the fund. And most VC's have multiple funds in play at any given time.

Semiconductor investing partners who hadn’t contributed to the success of the fund (that was most of them) either retired or were asked not to participate in the next fund.

The number of funds investing in semiconductor startups has shrunk significantly.

I saw the difficulties of raising capital for a semiconductor startup first-hand.

The market was pretty bleak when we started raising money in 2008. Combine a bleak market with The Great Recession, and it was really difficult to raise money.

Somehow we persevered.

We raised $12M in Series A funding in 2010 from two VC firms in the Silicon Valley.

There were 15 VC firms in the Silicon Valley I thought would be good candidates for our Series B round when we completed our Series A funding. I thought to myself, “Raising our Series B will be easy compared to raising our Series A.”

I was wrong. Dead wrong.

Things drastically changed between 2010 and 2013.

There were barely any semiconductor investors left in the Silicon Valley by the time we started raising our Series B funding in 2013.

We ended up raising our Series B funding in Florida, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and Texas.

There was no more Silicon in the Silicon Valley.

Less semiconductor investors means less new semiconductor companies.

The baton has passed.

The successful semiconductor executives of 1960’s and 1970’s became venture capitalists. They continued investing in what they knew: semiconductors.

That group of venture capitalists has been replaced by a new group: the successful software and internet executives of 1990’s and 2000’s.

And guess what?

They are investing in what they know:

Software and internet startups.

Call it a coincidence or whatever, but I look at many of the software app startups with no revenue being bought for large sums as similar to the semiconductor startups of the late 1990’s.

It’s a new bubble. I’m not the only one that sees a software bubble.

Mark Cuban and other others do too. Cuban wrote on March 4 that he believes the software bubble of today is worse than the tech bubble of 2000.

I don’t know whether today’s bubble is worse than the 2000 bubble. It’s just different.

The question is: will this group of investors be any smarter than the old group of investors?

Will software and internet entrepreneurs and investors learn from what happened with semiconductor investments?

Only time will tell.

What does future of the semiconductor industry hold?

Let’s go back to the basic rule of companies in an industry:

New Companies + Existing Companies – Merged Companies = Total Companies

There will be the odd semiconductor startup funded every year.

However the total numbers of companies will continue shrinking.

Merger Mania

We’ve seen a ton of semiconductor mergers over the last 24 months. Why?

You have a slow-growing market with too many companies. A way to grow earnings is with the increased efficiencies that come through consolidation. And we have one more thing:

Unbelievably low interest rates

Companies can finance their acquisitions through debt, so the consolidated company is accretive to earnings.

Add in the efficiencies you gain from laying-off employees and it makes sense why we are seeing so many mergers.

Could it be a great time to start a semiconductor company?

Think about it:

- There are still problems that need to be solved

- There is limited competition IF you can get funding

I tell the entrepreneurs I work with three things:

- You can do it.

- But you are going to have an insane advantage to get funded and win.

- You are going to have to knock on a lot of doors.

Do You Want To Grow Your Business? Maybe I Can Help. Click Here.

Graphic: Twitter

Picture: Depositphotos

Table: Courtesy of Wikipedia